In 2014 I was honored to receive the AIGA Colorado Robert Taylor Professional Grant to support a research project for a book on the 54-year history of the International Design Conference in Aspen 1951-2004. The funds helped me make three research trips to Chicago, Los Angeles and New York. This enabled three productive archive visits to the University of Chicago Library Special Collections, Chicago’s Newberry Library and the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles. I spent four days in New York City interviewing Aspen Conference leaders including long-term Aspen Conference board members Milton Glaser and Ralph Caplan as well as Aspen Conference speaker Massimo Vignelli just less than a month before his passing.

Why the topic of the Aspen Design Conference?

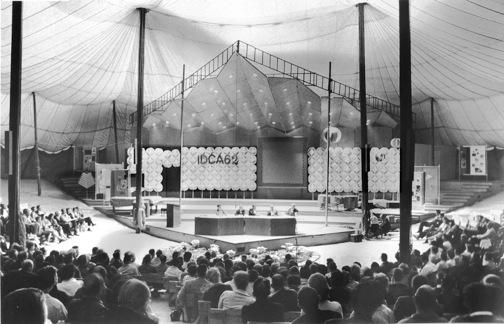

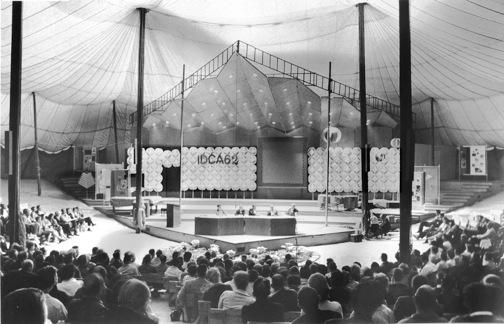

For 54 years, designers from across the U.S. migrated to Aspen, Colorado for a week of inspiration, networking, socializing and recreation. Between 1951 and 2004, the Aspen Conference’s quality and attendance blossomed, matured and declined. The conference’s outstanding speakers, topics, organizers, attendees and location quickly established it as a focal point of the international design community, focusing on an interdisciplinary spectrum from urban design and architecture to industrial design and graphic design. Social, cultural, technological and political content reached far beyond pragmatic and aesthetic design topics. Attendance grew from 200 to 2000 at its peak in the 1980s. Aspen became an annual pilgrimage to a mecca of design ideas that marked the beginning of every summer.

A panel discussion at the International Design Conference at Aspen, 1962

IDCA was led by a self-appointed board that chose each year’s conference chair and conference theme. By the late 1960s, Board members included prominent East Coast designers Eliot Noyes, George Nelson, Ivan Chermayeff, Milton Glaser, Lou Dorfsman, Henry Wolf, Ralph Caplan, Niels Diffrient, Jane Thompson, and Moshe Safdie as well as Californians Saul Bass, Jack Robertson and Richard Farson. This board of design luminaries staged a run of significant conferences but eventually exhibited a reluctance to refresh itself. In the later 1980s and 1990s conference themes became less rigorous, audience registration declined and conference costs exceeded revenues. Later efforts to rejuvenate both the board membership and conference programming proved insufficient and the last conference was held in 2004.

Today the International Design Conference in Aspen is more than a legend. Many current design leaders grew up at the Aspen Conference as students and young designers, shaping their lifelong practices. The conference was the catalyst for today’s design conferences, most notably Richard Saul Wurman’s TED Conference, which would arguably never have happened without Wurman’s Aspen conference and board participation.

Doing archival research

Archives are a whole alternate universe; serene, totally organized, and full of fascinating discoveries. Historical research feels like a detective novel. It’s amazing to hold a 70-year old handwritten letter that initiated a piece of design history. Hanging out in archives could be habit-forming!

The Getty Museum and library campus is an incredibly beautiful architectural masterpiece by architect Richard Meier; white and shining high on a Los Angeles mountainside. There, the Getty Research Institute is a rarified environment where you practically have to promise your first born for access! The Aspen Conference donated their archives to the GRI, and it contains boxes and boxes of conference board correspondence, meeting minutes, event photos, and conference publications. In addition to written documents, I looked for rare promotional posters and brochures produced in the conference’s early years by graphic design luminaries like Will Burtin, Leo Lionni, Lou Danziger and Paul Rand.

NYC graphic designer Ivan Chermayeff and British architecture critic Peter Blake, 1964

New York interviews

Interviews with former Aspen Board members, key presenters and annual participants are an important part of this book’s research. Sadly, many have already left this world including board members George Nelson, Saul Bass, Lou Dorfsman and Niels Diffrient. The New York City interviews were very touching and yielded many memorable quotes. Recordings of interview conversations provide important back-up for note-taking and I was very fortunate to have a “research assistant” to handle the recording. Jenny Taylor, then a Rocky Mountain College of Art+Design graphic design major in her last semester and an active AIGA Colorado member, had planned a trip to New York City to visit her graphic design mentor, Massimo Vignelli, who was in declining health. Fortunately Jenny was able to combine her visit to Massimo with this week of interviews and we had a great time dashing around Manhattan from one interview appointment to the next. Each of the seven interviews yielded rich information and could be an article on its own. Jenny and I were both struck by the feeling of “living history,” as we met with them. Here are a few highlights from three venerable design leaders.

Massimo Vignelli

The visit with Massimo was especially moving. He was seated at his famous massive stainless steel table with his Mac laptop adjacent to a dramatic two-story stained glass window with a gothic peak. As the evening dusk came on, we had a lovely conversation over tea. Massimo’s spirits were good; he was clearly delighted to have Jenny visit. But what gradually became apparent was that he was unable to rise from his chair and had become wheelchair bound. Within a month Massimo had left us and a chapter of design history had closed.

Jenny Taylor and Massimo Vignelli at the Vignelli residence NYC, April 24, 2014

photo by Katherine McCoy

Massimo and Lella Vignelli were featured presenters at the 1981 Aspen Design Conference “The Italian Idea” and received a standing ovation. Yet, in my archival research, I had read Aspen board reports and meeting minutes that indicated that Massimo had proposed for the Aspen board membership repeatedly in the mid-1980s yet was never invited by a board that appeared reluctant to bring in fresh viewpoints during this time period. Our time with Massimo provided the opportunity to ask him about that. His reply was that he was unaware of being nominated. Perhaps this was so, or perhaps this was a graceful and generous gesture over what may well have been an insignificant disappointment in a long and stellar design career.

Ralph Caplan

Our meeting with former Aspen Conference board member Ralph Caplan was a true pleasure. Ralph, an early editor of Industrial Design Magazine and long-term consultant to Herman Miller, has been described as “the scribe and the sage” of the Aspen board during his very long tenure from 1966 through 1988. His first appearance on the Aspen Conference program was in 1964, “Dimensions of Experience” chaired by Elliott Noyes. After a good laugh over his boyish good looks in a 1964 conference photo, he described meeting and debating with Reyner Banham, Jay Doblin, Lou Dorfsman, Wolf von Eckert, Cleveland Amory and Peter Blake. Ralph was impressed by this experience: “It wasn’t just the highest level of design discourse I’d encountered; it was the highest level of discourse in anything. I really admired Aspen.” Ralph chaired a particularly memorable conference program, “Making Connections,” in 1978 where Charles Eames gave his last public presentation.

Ralph Caplan, British architectural historian and critic Reyner Banham, and conference chair Elliot Noyes, 1964

Ralph praised the conference’s interdisciplinarity. “We always had a broad representation of other disciplines. One speaker told me, ‘I don’t know why I’m speaking at a design conference.’ Aspen was instrumental in getting designers to see what other disciplines had to offer, and vice versa.”

Regarding the board’s composition, Ralph described it as “self-perpetuating – we kept each other on.” Although Ralph and some other board members advocated more women on the board through the 1970s and 1980s, “there was a strong feeling that there were no worthy ones.” (The one long-term female board member through its peak years, serving from 1972 to 2000, was Jane Thompson, the first editor of Industrial Design Magazine, co-founder of the store Design Research and urban designer. Jane chaired four conferences and spoke at four others; it was Jane that organized the preservation of the Aspen Conference archives in the Getty Research Institute.)

Milton Glaser

We met with Milton Glaser in the upstairs front conference room of his East 32nd Street townhouse office of 50 years. Milton was invited to join the Aspen board in 1972 and chaired the next year’s conference “Performance.” He co-chaired two more conferences, “The Future Isn’t What It Used To Be” in 1983, and “Bare Bones” in 1991. No longer able to travel to Aspen’s high elevation, Milton resigned in 1993 after one of the longest tenures on the Aspen Conference board. Many of his remarks centered on the conference’s trajectory. When Milton joined the board in the early 1970s, it was a time of audience agitation for more relevancy and engagement. He recalls that “the conference was momentarily startled” and that Elliott Noyes, the Aspen board President and a leading U.S. industrial designer, resigned. “The conference became caught up in ideas of change. But it soon resumed its usual path with themes that recurred almost predictably.” Eventually “the conference got tired” and developed financial problems. Milton feels that conference programs came to be based more on the popularity of events rather than on serious content and that the board became “clubby” and failed to refresh itself. Milton observed that “Massimo seems like he would have been an obvious choice” for a new board member. Milton says that George Nelson (who served on the board from 1968 to his passing in 1986) “might have been the smartest person on the board – but the worst disposition!”

Milton Glaser at the Aspen Conference, 1983

Milton recalls the conferences with much pleasure: “They were a great social occasion for me. We met everyone once a year and it was a way to see people under wonderful circumstances. The barriers were minimal and everyone was accessible.” Although this was not actually the case with many of the Aspen board members, this was Milton’s practice – many designers fondly recall Milton’s informal and inspiring discussions with student groups under the aspens on the conference grounds.

In these interviews, the question always arose if there is a place for an Aspen Conference today. Ralph asked: “Would there be any need for it? A lot of what we hoped for has come to pass in design.” Milton remarked on the explosion of conferences today, with a “rotating cast of characters . . . . But maybe it’s not too late to invent a conference.” A revived Aspen would need to “invent a new form of address and open it to a larger subject, moving people to a larger consciousness.”

An ambitious vision. Yet this is a good description of what Aspen was at its best.

©2015 Katherine McCoy. All rights reserved.

Historic photos © James Milmoe. All rights reserved. Unauthorized reproduction of images is strictly prohibited.